You are your own archive

You Are Your Own Archive

–

An informal response to David Grubbs’ presentation “Remove the Records from Texas: Parsing Online Archives”, given at the Sound Art Theories Symposium at the School of the Art Institute, Chicago, Illinois, November 6, 2011.

http://depthome.brooklyn.cuny.edu/isam/publications/AMR/2011_Spring/article1.html

(quotations are taken from a transcript of Grubbs’ presentation at the symposium, not from the paper linked above)

–

–

Ubuweb’s Kenneth Goldsmith says “if it isn’t on the internet, it doesn’t exist”. Internet aside, can it exist if it hasn’t been described?

–

In my time as a creative individual, I have been involved with three international underground art networks: the mail art network, the cassette underground and the netlabel underground, each with its own culture, each having received different responses from academia.

–

My discovery of the mail art network was a personal revelation and an inspiration for me as a poor, young, creative person. I stumbled onto this network as a ‘zine publisher in the late 1980s, and I continued to work in the mail art net throughout the early 1990s. Via the free and open networking facilitated by the network, I met an large number of enthusiastic creative people, by exchanging art and ideas in written letters. I made some good friends who expanded my worldview and pushed me into creative directions I wouldn’t have otherwise followed. I became a prolific mail artist, mailing out uncounted scads of original work to every name and address I came across. This culminated in my assisting the brilliant mail artist Julee Peezlee in her 1993 mail art exhibition “Cold Snap”, a raw and non-academic approach to art curation with a punk aesthetic.

–

I was involved in this network for a few years. There was a lot of written documentation floating around the network, and I read all of it that came my way. I noticed over time that almost every piece of documentation mentioned about 4 or 5 different artists exclusively, and never made note of any of my favorite artists, none of the ones I knew. I sought out a few of these “famous” mail artists, and found them incredibly devoted to the networking aesthetic, incredibly giving of their time to any mail artist who came their way. John Held Jr. & Crackerjack Kid were great guys and especially good contacts to have, even if they were so connected with the whole wide network that you couldn’t necessarily get the level of friendly intimacy with them that you could with a lesser-known mail artist.

–

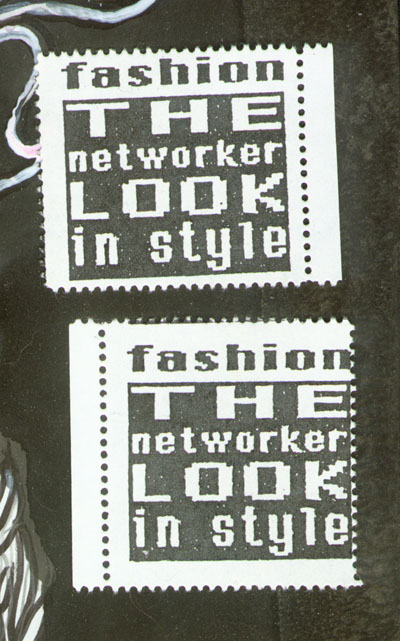

Over time, this exclusive focus on these few artists began to wear on me, these very few artists who had been canonized were great folks, but they were not the be-all end-all of mail art. When would some of the people I knew get their due? They wouldn’t, of course, these were essentially mail art invisibles. It seemed they were the mail art peasants, just goofing around, not serious. Not able to discuss or defend their work on an academic level. Merely practitioners. I found this narrow historical representation offensive and in an angry response I made my last pieces of mail art, an artistamp which had a stark black and white text stating “Fashion: The Networker Look in Style”, and another stating “I am One of the Mail Art Elite”. With these minor works, distributed to a very few friends, I quit the mail art network for good. I lost contact with many of my mail art friends, but I hope they are doing very well, I have very fond memories of them.

Over time, this exclusive focus on these few artists began to wear on me, these very few artists who had been canonized were great folks, but they were not the be-all end-all of mail art. When would some of the people I knew get their due? They wouldn’t, of course, these were essentially mail art invisibles. It seemed they were the mail art peasants, just goofing around, not serious. Not able to discuss or defend their work on an academic level. Merely practitioners. I found this narrow historical representation offensive and in an angry response I made my last pieces of mail art, an artistamp which had a stark black and white text stating “Fashion: The Networker Look in Style”, and another stating “I am One of the Mail Art Elite”. With these minor works, distributed to a very few friends, I quit the mail art network for good. I lost contact with many of my mail art friends, but I hope they are doing very well, I have very fond memories of them.

–

In the meantime, I had found something more personally appealing… the cassette underground. I had been nursing a desire to make music, and I found a group of people using the same network and barter method as the mail art network, but instead of visual art, they traded tapes. I networked the same way I had in the mail art culture, trading with countless artists, making deeper connections with some, and otherwise enjoying single, non-repeated trades with others. My first contact was Terry Burke of Set Cassettes, and not long after I met Ian Stewart of Samarkand / Bizarre Depiction, possibly through Terry, since this was also Ian’s first contact in the network. Ian ended up becoming one of the key figures of the cassette underground by starting a review / interview ‘zine called AUTOreverse which focussed exclusively on the cassette underground, (in the process documenting a small section of the history of tape trading). AUTOreverse followed in the footsteps of Jim Santo’s Demorandom column in Alternative Press and Gajoob magazine’s spotlight on work from the cassette network.

–

The cassette underground seemed to know that it was a unique phenomenon in the world… when I interviewed the noise artist PBK, whose real name is Phil Klingler, for AUTOreverse issue 12, he said: “What you are getting here is a post-modern response to technology, disenfranchisement and the complications of our age as we move into the 21st century. The cassette underground has created an important body of work, diverse as it may be, that is informed by, and draws from a whole 100 years of modern music theory, and also responds to millenial issues in a profound way. Some of the underground are getting better known, but there are many who dropped-out and disappeared. There is a wealth of obscure material out there, ripe for rediscovery. Guys like Carl Howard, Al Margolis, Jon Booth, Chris Phinney, any of those who had big tape labels, they must have hundreds and hundreds of tape-only releases in their collections, one day the musicologists will come knocking.”

–

This final print issue of AUTOreverse was publised in the Spring of 2001, well into the decline of the so called “golden age” of cassette networking, and as yet, the musicologists are still sitting on their hands. The efforts of someone like Carl Howard, whose important and influential tape label audioFile tapes released a massive and diverse collection of weird jazz, rock and noise with attractive tape covers and a fully realized label “personality” has essentially disappeared to history. After a catastrophic computer crash destroyed Howard’s own personal archive in 1999, the label abruptly ceased operations. “Watch fifteen years of ones life vanish… before… your… very… eyes!” Howard emoted during an interview with AUTOreverse online magazine.

–

Where is the Wikipedia entry for audioFile records? At least there is one for a minor football personality sharing Howard’s name. Phew, we don’t want any of that important minor sports trivia to pass out of our collective memory!

–

Neither is there a Wikipedia entry for someone like Zan Hoffman, an extremely prolific artist active in the cassette underground, and still active today, whose thousand-plus releases on extremely limited release cassette and CDr have included uncounted thousands of collaborations with artists of both the ‘notable’ and the extremely obscure branches of the musical underground, somehow, his almost inconceivably vast body of work is just not important enough for Wikipedia, nor for academic research. Why not?

–

Well, why would anyone care? The cassette underground were just a bunch of failed rockstars, pretending they could actually make music, right? The cassette underground wasn’t serious. Not serious music, not serious people, it’s okay if this thing is skipped over, no one needs to write about it, it wasn’t serious, nothing can be learned from it, get it out of my face.

–

After the advent of the internet essentially destroyed the cassette underground network in the early 2000s, and after it began to reform itself in the early 2010s, Don Campau, himself a longtime participant in the cassette network, took it upon himself to document and archive the experiences of those involved in the cassette underground, I’m sure as a reaction to noticing the obvious lack of interest from academia, popular culture and pretty much everyone not thus far described. The cassette culture had to archive itself or else it would disappear to history. Campau’s “The Living Archive of Underground Music” began in November of 2009, and, as he notes in an email, was conceived “not as an academic history, but as a personal reflection.” The website contains brief interviews and essays from many of the personalities who had been involved in the cassette underground, each giving personal accounts of their experiences. As Campau describes in the mission statement of the Living Archive website: “Simply put, “Cassette Culture” was a group of individuals worldwide who recorded their own music at home and distributed it themselves. This all began at the beginning of the 1980’s when home recording devices became affordable and cassettes were plentiful and cheap. These were not “demos” but fully realized art projects primarily traded with other like minded artists around the world. This was a decentralized scene although there were publications that addressed it at the time.”

–

Noting the near impossibility of archiving the cassette underground’s activities, especially so long after the fact, Campau’s mission statement is humble: “The Living Archive is not meant as a comprehensive history but more about my personal relationship with the people who participated in this home recorded music scene. That being said, there is a history to be gleaned from these memories and of the others who have helped me out here.” Campau is filling an important void in the archiving of the history of the huge output of this art network, but in some senses the cassette underground is being underserved by this single individual’s efforts. In asking Campau if he knew of other efforts to preserve the history of tape culture, he noted the online forum at http://cassetteculture.net and also the work of (curiously enough) mp3 blogs.

–

Academia has ignored this subcultural phenomenon for the most part, perhaps now that someone has begun to archive some of the personal histories of these tape traders, this will change. On the other hand, is it perhaps a good thing to be ignored? The danger exists of non-authorities who become authorities by dint of being the only one writing about a subject, this could lead to a focus on a select few artists who would then be described for posterity, and the remainder of artists would be alluded to in the vaguest possible way. “This important person did this, this important person did that… and other stuff happened (unimportant by implication)” Follow up academic research might echo this approach, citing the previous paper, naming the same names, and then an echo chamber effect would set in, elevating the work of a few, and ignoring the huge number of artists who poured their creative lives into this medium, and into this culture. Is this better than being forgotten?

–

This nightmare scenario is not what happened in the mail art network, each of the “famous” people in the network were doing very important work to document the movement from within, so they deserved all the credit they got. The problem existed that very few scholars delved any deeper, which is still an injustice.

–

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the growing access to the internet, not to mention the affordable access to CD-r recording technology sent the cassette underground into a decline that all but destroyed it for a time. The letter writing and tape trading that people had engaged in for decades suddenly seemed hopelessly antiquated with the ease of email.

–

It was a confusing time for me, personally. I was still interested in the personal connection that could be had with a trade of a physical product, so I clung to the CDr media for a while. I set up my label, Vuzh Music, online with a catalogue of purchasable CDrs, and an open invitation to trade. I began a project called Vuzh Underground Editions, which re-released some of my favorite recordings from the cassette underground on CDr. Eventually I grew frustrated with the unreliability of the CDr medium, and felt guilty about selling and trading such a flawed product. I happily migrated my whole catalog into the netlabel underground when it began, and I haven’t regretted it a bit.

–

The netlabel underground sprang up organically, and curiously contained among its participants very few who had been involved in the cassette underground, certainly no one I had known. Home recording musicians who might at a different time have joined the cassette underground, instead saw the internet as an easy and quick way to transfer their work from composer to listener directly, without having to produce a solid object to mail off. From the earliest days of the netlabel phenomenon, artists gave their work away for free, primarily in the mp3 format. Netlabels rapidly adopted the Creative Commons as a new form of licensing upon its founding in 2001 by Lawrence Lessig, Hal Abelson and Eric Eldred. With its focus on attribution of authorship, in opposition to the tradeable ownership certificate of the copyright, the various Creative Commons licenses offered netlabels a working model for pridefully claiming authorship of a commercially-free product that nevertheless held value.

–

Where the cassette underground was based upon a barter system, a tape for a tape, or a CDr for a CDr, a letter accompanying each… the netlabel underground eschewed the barter system being that there was no physical object to trade. The best way to distribute your music, if you were an unknown artist, was to give it away for free, the fewer barriers the better. The standard American dream of the rock and roll musician: “submit a demo, get signed, record an album, get your promo photos done after teasing your hair up & wearing special clothing, tour, become famous, screw lotsa groupies, do drugs, get STDs, be interviewed by Rolling Stone magazine, live happily ever after” had been completely subverted in favor of the more straightforward model “record the music that you want to, no matter what it sounds like, release it for free, if someone digs it, then cool… if not then fuck ’em”, a sentiment originating in the cassette network.

–

Sadly however, by making music available over the internet, the one-on-one networking and letter exchange of the cassette underground -the human element- was lost. For me, though, it was better to have anonymous downloaders accessing my music without any comment than no one at all. Even if there wasn’t a community and there wasn’t much networking, the netlabel model was, I felt, the best there was at the time for an unknown experimental, electronic composer of abstract music.

–

With the rise in popularity of social networking tools Twitter and Facebook in the late Zeroes, however, the community aspect of the netlabel underground did finally begin to form. Having started with an “everyman for himself” attitude, netlabels and artists naturally gravitated toward connectivity, at first to grow the base to whom they could promote their own releases, and later to share experiences and thoughts with their colleagues on creative work in this new framework.

–

Netlabels took some of their form from the standard music label model, but at a more homegrown, DIY level: individuals curating collections of musical releases based on a set of highly personal aesthetic values. There are netlabels for ambient music, noise, dub, abstract experimental, pop music, and probably any other genre you can think of. Each label with its own personality, Just Not Normal, Earth Mantra, Modisti, BFW Recordings, Petcord (just to name a few at random that I personally have enjoyed) each have their own unique flavor based on the curatorial preferences of the label heads. While the promotional focus is always on the newest release, the older releases remain available in perpetuity for free download (in most cases). The netlabel list maintained by David Nemeth at the Acts of Silence blog lists over five hundred netlabels at the time of this writing.

–

November 5th & 6th, 2011 I attended the Sound Art Theories Symposium, hosted by the School of the Art Institute in Chicago, Illinois. I attended as part of my research into sound art with the goal of curating an exhibition in the Spring of 2012 as a student project, an independent study which grew out of the Museum Studies class taught by Jennie Kiessling at Front Range Community College in Fort Collins, Colorado.

–

Among the thirteen presentations at the symposium was one by David Grubbs, Associate Professor in the Conservatory of Music at Brooklyn College, CUNY, former member of the rock groups Gastr del Sol, Bastro and Squirrel Bait. Grubbs’ presentation was titled “Remove the Records from Texas: Parsing Online Archives”

–

Grubbs describes the concept of archive as being in flux with the advent of the internet, with websites like Ubuweb, and various mp3 blogs serving as new kinds of archives, making available otherwise rare or impossible to find experimental music, film and various documents. These online archives do not by any stretch offer the promise of eternal availability, as is usually expected with an archive. As Grubbs notes “Unlike online sources that stream only content, Ubu allows its users to download its files. Ubu makes no promises about its futurity, and the point, the unspoken point seems to be a desire that files should be downloaded and saved and not be presumed to float in the data cloud in perpetuity.”

–

Grubbs’ presentation included a description of online archives as reducible to three forms: “1.) Online archives, authorized or not, organized around a particular artist, an institution or the vision of one or more curators, 2.) Blogs that are usually the work of a single individual, that are more informal, but often substantial in terms of the amount of recordings hosted, and 3.) File sharing that occurs with little or no contextualizing apparatus.”

–

Where, I wondered, are the netlabels in this description?

–

If the definition of archive is fluid enough to contain mp3 blogs and Ubuweb, both of which are iffy when considering futurity, and both of which collect contemporary work from the ‘now’, if we’re considering online archives of experimental sound, then why are netlabels excluded?

–

Grubbs explains: “In the chapter entitled ‘The Historical A Priori and the Archive from the Archaeology of Knowlege’, Michel Foucault describes the archive as fundamentally separate from the discourse of the present. In Foucault’s words the archive is ‘a privileged region, at once close to us, and different from our present existence. It is the border of time that surrounds their presence which overhangs it and which indicates its otherness. It is that which outside ourselves delimits us. It is not possible for us to describe our own archive since it is from within these rules that we speak.’ Now, adhering to Foucault’s fundamental distinction, that the archive is separate from the present that the archive defines the discourse of the present through the separateness, it would seem inapt to speak of any of these examples as archives. They participate in the discourse of the present by circulating work made by living artists.” So obviously, some forgiving is being done to include Ubuweb, and mp3 blogs into the category of archives, but this same generousness isn’t expansive enough to include netlabels?

–

I had an emotional response upon hearing this presentation, and confronted Grubbs, ineloquently, with my concerns; however, in reflection, my beef is not really with him or his presentation at all. I suspect (although he did not explicitly admit this) that Grubbs may have simply been ignorant of the netlabel underground, and not, as I had concluded in the heat of the moment, that he excluded them because netlabels are not serious, are comprised of silly, goofy people pretending to be composers of experimental music, not in his purview, get it out of his face. Given my experience with academic documentation of the mail art underground, and the cassette underground, this highly suspicious and emotional response from me was to be expected, I suppose, perhaps overly earnest and undisciplined, but hey, that’s me.

–

In a brief discussion with Grubbs after the presentation, he defended his exclusion as primarily an instinctive place to draw the line for the purposes of his paper, and suggested that the difference may be that archives collect primarily work otherwise unavailable from the past and that netlabels don’t seem much different from standard labels in making available primarily new work, (never-minding that mp3 blogs sometimes collect and make available some work so new it hasn’t yet been officially released) He requested more info from me and feeling rather intimidated I kinda choked up. I feel like an idiot for stumbling all over my own words and not making a watertight case for netlabels when the perfect opportunity arose. Some ambassador for netlabels I am!

–

The fact remains that there is a level of perceived amateurism that excludes netlabels from “serious” consideration. Ubuweb, (from my perspective I find this strange), considers itself an amateur operation. Grubbs’ presentation quotes Ubuweb founder Kenneth Goldsmith: “We know that Ubuweb is not very good, in terms of films the selection is random and the quality is often poor, the accompanying texts to the films can be crummy, mostly poached from whatever is available on the net. Ubu is a provocation to your community to go ahead and do it right, do it better, to render Ubu obsolete.” I somehow doubt, however, that Ubuweb would deign to archive the work of any currently practicing netlabel artist… is it because netlabel music exists on an amateur stratum below its own? I suspect this may be partially the explanation, but the more important one is that Ubuweb probably recognizes that netlabels themselves are their own archive, and they don’t need Ubuweb to document their history. (Yet?)

–

Are netlabels archives?

–

Thomas Park, who records under the names Mystified and Mister Vapor, (to pick one good example from among very many who would just as easily fit the bill) has a mission for near total availability of his own prolific creative work. By his estimation about 80% of his entire body of work (no accurate discography exists online of Park’s prolific work, so it’s impossible to give a count) is currently available on some format, about 80% of that hosted on about two dozen netlabels. Of the work that’s not officially available, he says, the work is still accessible and can be sent out to interested listeners upon request in any format they desire. As anyone who is involved in the netlabel underground can attest, Park is a tireless artist, and even more tireless when it comes to assuring the availability and public awareness of his output. Is he merely a self-publishing artist, is he not the archivist of the work of Thomas Park? Who else is going to archive the work of this artist?

–

David Nemeth’s recently initiated blog “the Easy Pace” is essentially a monthly aggregator of new releases in the vast netlabel landscape, with artist, titles and cover art presented along with a link to the main release webpage. As long as this project continues, it provides a wealth of quantifiable historical data documenting the releasing activity of the scene. While only going back to August 2011, its intentions could be easily divided between alerting potential listeners to new music and archiving the information for the future. Other similar aggregators exist (although Nemeth’s is the most informative by including cover art) and hopefully in comments some people will list some of these others.

–

And what of netlabels themselves, each housing their own unique catalogs stretching back to the beginning of the movement? The promotional focus may be on the newest work, but these sites continue to host the older works and assure their availability on the same terms of service as the new work. Who else is going to store this stuff for history but the labels that originally released it? Nemeth points out in an email “Very recently Abracadabra went silent and now all their releases are gone. They didn’t use archive.org or sonic squirrel etc. Meanwhile, look at Digitalbiotope (one of my favorite dead labels), all their stuff is still available.” When a netlabel goes dark, sometimes another will pick up their catalog and sometimes the label acknowledges itself as an archive and stays live, but unchanging, but sometimes the material is simply lost for good, because no other functioning archive exists.

–

I guess what I’m really shooting for with this blog post is a wake-up call to the netlabel underground, much more this than some demand of attention from the academy. Are you going to wait for the bearded men in the corduroy suits with elbow patches to describe your history? Are you going to wait until the fog of time clouds your own memories before bothering to document your history? Netlabels are a significant phenomenon, the music and culture are unique and important to this time in history, whether or not popular culture, or the academy notices it. This thing you are involved in matters, and it belongs to you.

–

Will a Don Campau of netlabels arise? Will scads of netlabel versions of Don Campau’s archive arise? Will we allow more netlabel catalogs to disappear with nothing more than a shrug of the shoulders? Will we begin to write our own history in such a way that it is less likely to be misrepresented? Where do we even start? Well, I can suggest one thing: what about that Wikipedia entry on “netlabels”, are we all happy with that description that someone else has written about our culture? If not, then what are we going to do about it?

–

And then, more importantly, what next? You tell me.

–

–

–

–

Postscript added 11/16/2011:

David Grubbs has responded in an email to the question of whether the exclusion of netlabels in his paper was intentional :

–

“Thanks so much for sending me the link to your post. I really enjoyed it and I learned a lot from it. You are absolutely correct that I didn’t understand the reference to netlabels. To be frank, it wasn’t even a term that I was familiar with — and you (and one of the folks in the comments section) are right that my not considering netlabels within the context of the category “archive” comes entirely from my unfamiliarity with the practice.”

–

This brings up another point that I don’t touch on in this essay, but have frequently stated in other forums, and that is that -as a community- it is needed for us to stop ONLY self-promoting, and begin to raise the overall awareness of the whole netlabel underground. Using all of your efforts only to promote yourself while ignoring the frame on which you hang your own work is a disservice to the whole community, and ultimately a disservice to yourself. Raise awareness of the netlabel underground and we ALL benefit.

–

Do you think you’re just some brilliant composer flying solo, or are you part of an international cultural movement? If you’re a bootstrapper then good for you hope you do well, but I’m probably not interested to follow your work anymore. I’m proud to benefit from the netlabel community, and I will do what I can to boost it whenever I can.

–